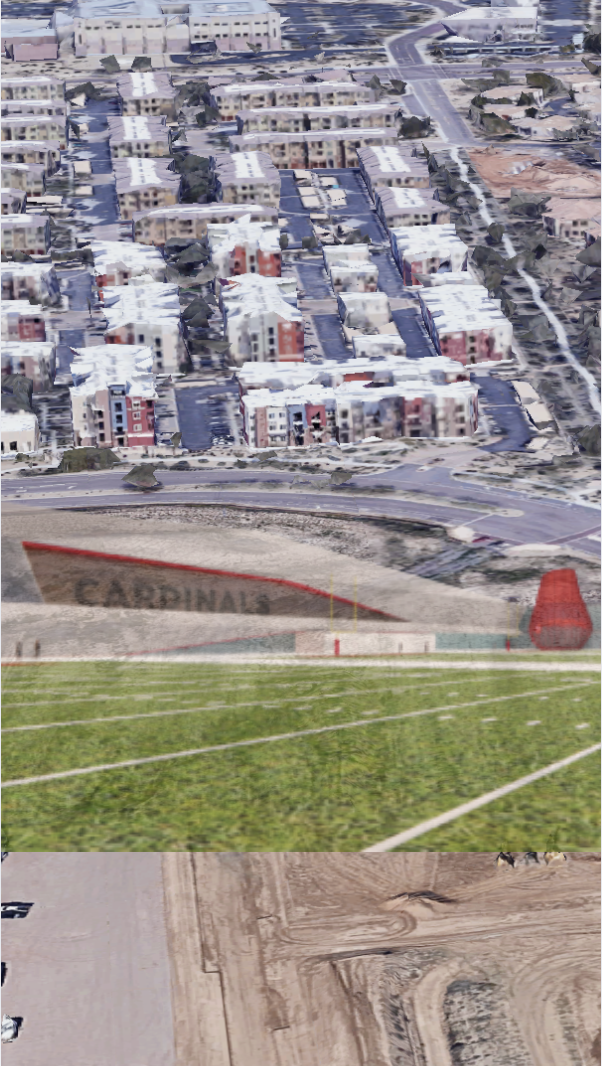

In mid-2025, Mortenson Development—a Minneapolis-based firm—emerged victorious in a high-stakes Arizona State Land Department auction, securing a 217.16-acre parcel in north Phoenix for $136 million. This land sits at the northwest corner of Scottsdale Road and Loop 101, straddling a dynamic zone between Phoenix and Scottsdale and abutting growth corridors already under transformation.

Historically, this parcel had drawn attention as a prospective home for the relocated Arizona Coyotes NHL franchise. That plan, however, dissolved when the franchise moved to Utah and the arena ambitions were abandoned. Now Mortenson is positioning itself as the master planner, proposing a mixed-use development that reimagines the land as a 21st-century urban node.

This auction matters because it signals a new chapter in Phoenix’s north corridor: reclaiming large raw land parcels for integrated, dense mixed uses, rather than piecemeal sprawl. It also underscores how state land auctions are being used as a lever in metropolitan growth strategy. In areas like Desert Ridge, Paradise Valley, and in the burgeoning North Gateway, developers are jockeying for scale. The Mortenson deal is now a bellwether for how Phoenix may absorb expansion over the next decade.

The opportunity here is not just acreage, but platform. The challenge in Phoenix’s growth narrative has always been: how to stitch new development into existing mobility, infrastructure, and floodway systems without generating inefficiency or overspending on off-site improvements. That balance often kills projects before they begin. But in this case, Mortenson’s acquisition gives them the leverage: they can tailor infrastructure, phasing, and land use from the ground up. That aligns with both public and private incentive.

Imagine building a campus of modern offices, entertainment, retail, and residential interwoven with open space, all configured to minimize auto dependency and maximize connectivity. That solves for location risk, market absorption, and resilience. The site’s visibility and accessibility (Loop 101, Scottsdale Road) sharpen the proposition for anchor tenants. And because the floodplain mitigation (via the Paradise Ridge Wash improvements) is baked into the plan, Mortenson can unlock more usable land while providing broader systemic benefit.

From a developer’s viewpoint, that’s a high-leverage play: if the phased build is executed well, returns can compound as later phases finance earlier ones. For the city and public sector, the upside is densification, increased tax base, and better alignment of infrastructure with growth patterns. For investors and future tenants/residents, it becomes a locus — a new “place” rather than an isolated project.

When we talk “mixed-use,” there is a spectrum: you might lean heavier on office, or tilt toward residential, or package hospitality or retail as connective glue. Mortenson’s preliminary public filings suggest a balanced mix—office, retail, restaurants, entertainment—with a first phase anchored by a 30-acre campus of about 350,000 square feet. That suggests a hybrid model rather than pure speculative office or pure multifamily development.

One variation is a “campus + live/work” model, where office buildings share podium parking with residential units above, and ground floors activate with retail or food/amenity space. This fosters 18-hour activation, mitigates vacancy risk, and better optimizes land. Another is the “urban node” model: mixed towers around a central plaza, where different uses feed each other. But the tradeoff is complexity: phasing, parking, shared services, and coordination become harder. Too much office in a downturn can drag; too much residential without demand kills absorption.

In terms of homeownership and equity, the way Mortenson phases residential components (if any) will matter. If they mix for-sale (townhomes, condos) with rental, they can capture both equity value and cash flow. But if they lean wholly rental or leaseholds, much of the wealth accrual stays with the developer. Also, the mitigation of flood zone and infrastructure costs up front can reduce marginal burdens on future homeowners, making the units more affordable (in relative terms). The balance between “prestige” product and attainable housing will be a tension to manage.

From a long-term equity stance, local stakeholders and anchors (small businesses, public amenities) should be woven in early so the place doesn’t feel like a gated enclave but a genuine node. The best mixed-use developments globally show how public spaces, transit stops, community programs, and local retailers anchor value beyond square feet.

On the municipal front, Phoenix City Council has already begun engaging. In late August 2025, the Council moved forward to consider a development agreement for public infrastructure with Mortenson, setting a 12-month window for negotiation. The City will reimburse certain improvements (excluding the $30 million Paradise Ridge flood mitigation component) up to developer cost, creating a public-private cost balance.

Maricopa County’s role is also critical via flood control and drainage oversight; the Paradise Ridge Wash flood mitigation is a county-scale project that intersects Phoenix, Scottsdale, and adjacent jurisdictions. The state land department (Arizona State Land Department) also retains certain oversight and restrictions as part of the auction conditions and infrastructure requirements.

Among players, local developers, architects, and firms such as Speedie & Associates (which prepared the environmental assessment) are part of the early ecosystem. In the real estate community, firms in Paradise Valley, Desert Ridge, and the North Gateway corridor are watching closely: many see this as a signal of where institutional capital is going next. Some local brokers and analysts see the Mortenson move as validation that large, raw infill parcels in the loop will attract “city-scale” development rather than pure residential subdivisions.

Voices in community groups and neighborhood associations will matter too—concerns over traffic, access, scale, and infrastructure are inevitable. As with past developments along Scottsdale Road and 101, neighbors will demand transparency and mitigation. The developer will need to engage early and often.

To maximize success, Mortenson (or any developer entering similarly sized infill parcels) should anchor the project with phased flexibility: the first phase (office campus, retail spine) must be built to stand alone, with connectivity and services that allow future phases to plug in seamlessly. The 30-acre campus is a smart starting point.

Second, the unlocking of land via flood mitigation must be prioritized early. The Paradise Ridge Wash improvements are not optional, and are being treated as foundational infrastructure. Mitigating flood risk will materially increase usable acreage and reduce insurance or constraint burdens downstream.

Third, create a mobility plan that emphasizes multimodal access (pedestrian, micro-mobility, shuttles, transit connections) rather than overbuilding first-phase parking. In Phoenix’s climate, shaded walkways, water features, and microclimate design will boost activation and desirability.

Fourth, layer in local partnerships and placemaking programming early — retail incubators, makerspaces, coworking pods, cultural or arts nodes. That soft infrastructure helps embed the development in the broader Phoenix narrative rather than “just another master plan.”

Finally, align exit or hold strategies: plan for a mix of sell-down (for-sale units or condominium components) alongside retained income assets (office, parking, retail). That dual strategy helps manage risk and capital cycles.

The Mortenson 217-acre acquisition is more than a land buy—it’s a manifesto for how Phoenix’s next wave of growth may be constructed: integrated, infrastructurally conscious, and strategically phased. But the path from raw land to vibrant district is fraught, requiring alignment with public partners, mitigation of environmental constraints, and a disciplined mix of uses.

This is not a plug-and-play parcel; it's a test bed for modern urbanism in the Sonoran desert. Developers, municipal planners, neighborhood leaders, and future residents all have a role in shaping this destiny.

Before you pursue a project of this scale, consult with licensed local land use attorneys, civil engineers, flood control authorities, and municipal planners early in the process. This narrative is offered as strategic input, not legal or engineering advice.

As Phoenix grows, will this parcel become the new heart of North Phoenix or simply another monolithic campus? And how will it influence the next wave of infill development in Maricopa County?

Arizona Cardinals’ $136 Million “Headquarters Alley” Project: How a 217-Acre Deal Will Redefine North Phoenix by 2028

Arizona Cardinals’ $136 Million “Headquarters Alley” Project: How a 217-Acre Deal Will Redefine North Phoenix by 2028 Exploring Arizona’s Unique Land Ownership Laws: What Every Future Homeowner, Investor, And Relocating Professional Needs To Know

Exploring Arizona’s Unique Land Ownership Laws: What Every Future Homeowner, Investor, And Relocating Professional Needs To Know

Public Safety as an Asset Class: The New Scottsdale AdvantageIn today’s Smart City economy, safety isn’t simply about peace of mind—it’s becoming a measurable, marketable asset class. Scottsdale is proving that public safety can be engineered into the fabric of

Public Safety as an Asset Class: The New Scottsdale AdvantageIn today’s Smart City economy, safety isn’t simply about peace of mind—it’s becoming a measurable, marketable asset class. Scottsdale is proving that public safety can be engineered into the fabric ofNice to meet you! I’m Katrina Golikova, and I believe you landed here for a reason.

I help my clients to reach their real estate goals through thriving creative solutions and love to share my knowledge.